Review: Art confronting atrocities – there are Seeds of Hate and Hope at the Sainsbury Centre, Norwich.

Seeds of Hate and Hope: A Powerful Exhibition on Human Conflict and Resilience

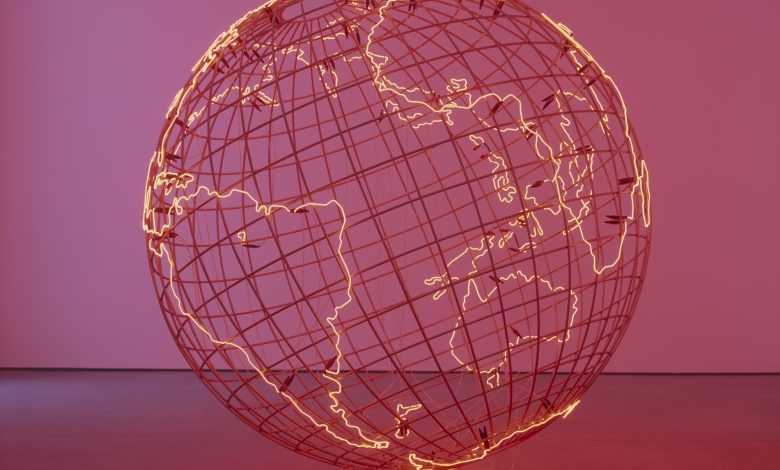

As you enter the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich, a large globe with red-outlined continents emits an ominous glow, immediately setting the tone for the “Seeds of Hate and Hope” exhibition. Part of the provocatively titled “Can we stop killing each other?” season, this free exhibition running until May 17th offers a profound meditation on humanity’s darkest moments and our capacity for healing. Mona Hatoum’s buzzing globe, created in 2009, serves as a fitting introduction to a collection that examines genocides, ethnic cleansing, war crimes, and crimes against humanity across different eras and regions. The red light bathes visitors in a color that humans instinctively associate with danger—a subtle yet effective primer for the emotional journey ahead.

The exhibition doesn’t shy away from confronting visitors with the brutal realities of human conflict. Ishichi Miyako’s haunting photographs display damaged clothing—ghostly remnants of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that silently testify to the lives abruptly ended. Jakkai Siributr’s military uniforms appear conventional until you peer inside the camouflage hats to discover images of weeping women against backgrounds of flames, powerfully representing the plight of refugees at the Thai-Myanmar border. Alfredo Jaar’s chronological display of Newsweek covers from the beginning of the Rwandan genocide until it finally made the front page serves as a damning indictment of media priorities and Western indifference. These works force us to witness atrocities that are often sanitized or altogether ignored in mainstream discourse, challenging our comfort and complacency.

Despite its unflinching look at human cruelty, the exhibition balances darkness with acts of creative resistance and redemption. Gideon Rubin’s methodical redaction of every page in Hitler’s “Mein Kampf” symbolically erases the dictator’s poisonous ideology, while Indre Serpetyte transforms ISIS propaganda videos into abstract geometric arrangements reminiscent of Mondrian’s work—reducing instruments of terror to mere blocks of color stripped of their power to intimidate. These artistic responses demonstrate how creativity can serve as a form of resistance against hatred and violence, offering alternative narratives to counter those of the perpetrators. By transforming objects and symbols of hatred into art, these works suggest the possibility of transcending cycles of violence through creative engagement with our painful histories.

The exhibition features both internationally recognized artists and lesser-known but equally powerful voices. William Kentridge contributes a film confronting South Africa’s apartheid legacy, while Denzil Forrester presents a moving drawing of his friend who died in police custody. Perhaps most affecting are works by artists like Peter Oloya, a former child soldier in the Lord’s Resistance Army who now creates sculptures as part of his healing process. Zoran Music’s figurative drawings, created while imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp, offer a firsthand witness to unimaginable suffering. These diverse perspectives ensure that the exhibition doesn’t present atrocities as abstract or distant events but as lived experiences with profound personal dimensions. Through these individual stories, visitors connect emotionally with historical tragedies that might otherwise remain academic or impersonal.

What distinguishes “Seeds of Hate and Hope” from many exhibitions on similar themes is its meticulous curation by Tafadzwa Makwabarara and Jelena Sofronijevic, who have assembled works that collectively build a narrative more powerful than any single piece could achieve alone. Unlike typical exhibition experiences where only a few artworks leave a lasting impression, nearly every work in this collection demands emotional and intellectual engagement. The curators have created a space where art serves not merely as aesthetic objects but as vehicles for confronting difficult truths about humanity’s capacity for both cruelty and compassion. The exhibition’s impact lingers long after viewing, prompting continued reflection on personal and collective responsibility in the face of atrocity.

The exhibition opens with George Santayana’s famous warning that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”—a philosophical foundation for the entire collection. “Seeds of Hate and Hope” lives up to this premise by refusing to let visitors forget historical and ongoing atrocities from across the world. Yet as its title suggests, the exhibition ultimately balances its unflinching examination of human cruelty with glimpses of resistance, resilience, and the potential for transformation. In documenting both the depths of human hatred and our capacity for hope, the exhibition invites us to consider how confronting our painful past might help us create a more just future. In a world where conflicts continue to rage and new atrocities emerge with disturbing frequency, this exhibition offers not easy answers but a necessary space for contemplation and reckoning with our collective humanity.